A Pictorial Biography of Arthur Vidich

This site is dedicated to the life and times of Arthur J. Vidich, an American Sociologist and Anthropologist who lived from 1922 to 2006.

Tuesday, January 19, 2021

Vidich and Bensman - A Rare Collaboration Captured in Pictures

Arthur Vidich and Joseph Bensman worked together on many books over a period of over twenty five years. This extraordinary collaboration brought together two men whose sociological skills worked seamlessly together to create some of the most important critiques of American society in the twentieth century. These rare photos of them working together were taken by Paul Vidich, Arthur Vidich's son, when the two men were completing the final manuscript for American Society - The Welfare State and Beyond. Their sense of comradeship and ability to work together was much admired by his family and many of his students. While they were highly disciplined researchers and writers they also knew how to enjoy each other's company as is clearly seen in this series of photos taken one evening while they took a break from the final editing work on their manuscript. These photos were taken at Arthur's home at 40 Beford Street in Greenwich Village circa 1974.

Saturday, January 11, 2020

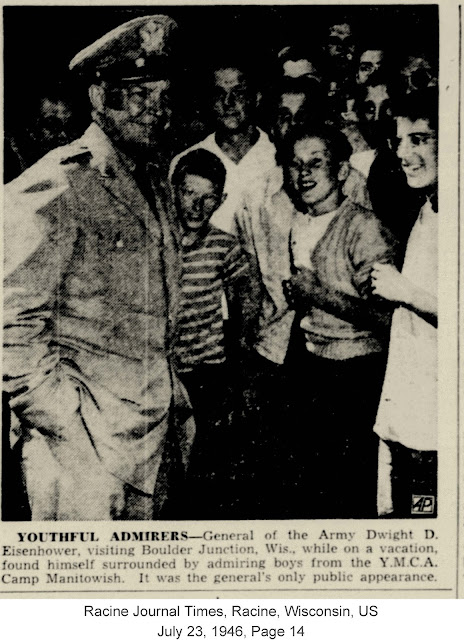

General Eisenhower Creates A Sensation - Visits Vidich at YMCA Camp Manitowish

Saturday, January 26, 2019

The Intellectual Legacy of Arthur Vidich - His Literary Network

Arthur Vidich was asked to write the introduction to many books in

the field of sociology - especially ones that focused on his passion for community studies, politics, culture and the role of the intellectual in modern society. Many of his students asked for such favors when publishing their first book but similar requests were made by friends and colleagues who valued his professional opinion. This posting reviews three of the most significant reviews Art prepared for his close friends - Hans Speier, Ahmad Sadri and Rita Caccamo.

Intellectuals as Change Agents

Vidich wrote the introduction to Ahmad Sadri's Max Weber's Sociology of Intellectuals, published in 1992. In it he praised Sadri's gift for bringing "order to a subject that up to now has defied the best efforts of social theorists." Are intellectuals simply the product of the social and economic forces in which they live or can such persons rise above these material distractions and view the world dispassionately? In an age of propaganda driven by the vested interests of power cliques and social and political forces, it is often very difficult to determine the motives of intellectuals within our society. Sadri's book, according to Vidich, expands on Max Weber's theories concerning the role of intellectuals in modern society and establishes an entirely new framework for organizing intellectual traditions. As Vidich explains, Sadri "ingeniously provides a way to differentiate such diverse types as scientists, scholars, theorists, theologians priests, bureaucrats, media specialists, reformers, lawyers and revolutionaries by their attitude and function." While Sadri's writing may at times be ponderous, it is a masterful treatment of the role of intellectuals in modern society. As Vidich concludes, Sadri's "formulation of a heuristic general theory of intellectuals and intelligentsia is independently significant, a major contribution to contemporary social thought."

Vidich wrote the introduction to Ahmad Sadri's Max Weber's Sociology of Intellectuals, published in 1992. In it he praised Sadri's gift for bringing "order to a subject that up to now has defied the best efforts of social theorists." Are intellectuals simply the product of the social and economic forces in which they live or can such persons rise above these material distractions and view the world dispassionately? In an age of propaganda driven by the vested interests of power cliques and social and political forces, it is often very difficult to determine the motives of intellectuals within our society. Sadri's book, according to Vidich, expands on Max Weber's theories concerning the role of intellectuals in modern society and establishes an entirely new framework for organizing intellectual traditions. As Vidich explains, Sadri "ingeniously provides a way to differentiate such diverse types as scientists, scholars, theorists, theologians priests, bureaucrats, media specialists, reformers, lawyers and revolutionaries by their attitude and function." While Sadri's writing may at times be ponderous, it is a masterful treatment of the role of intellectuals in modern society. As Vidich concludes, Sadri's "formulation of a heuristic general theory of intellectuals and intelligentsia is independently significant, a major contribution to contemporary social thought."

Community Studies - An Anthropologist's Perspective

Arthur Vidich praised Rita Caccamo's Back to Middletown as one of the finest examples of applying an anthropologist's "outsider perspective" to the critique of American communities. For those familiar with American community studies, the two landmark works by Robert and Helen Lynd, Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture and ten years later, Middletown in Transition (1937) established the first reference points for the decline of small town communities in America. Vidich's own work, Small Town in Mass Society, followed in that tradition so his review of Cacamo's book was more than an academic favor for a colleague. Vidich, trained both as a sociologist and anthropologist, recognized the unique insights that Caccamo, an Italian intellectual, displayed in her reassessment of Muncie, Indiana - the town the Lynd's called "Middletown." Vidich explains the unique journey that brought an Italian intellectual to study an American community that has probably been more studied and critiqued and re-critiqued of any community in America. Why do it? Caccamo's motives were multi-fold and the reader will need to read this book for the clues. Perhaps more important were her findings; she concludes that the Lynd's completely overlooked many salient trends in Muncie community life that were not pertinent to their review of the older community values. Vidich was deeply impressed by the insights that an outsider like Caccamo could bring to Middletown studies. He considered it a "benchmark study" that vies with the Lynd's original work largely due to the value of taking a fresh look at issues that only an outsider could see.

Is there Truth in Hell?

Hans Speier was one of Arthur Vidich's dear colleagues at the New School for Social Research. Hans was a man of strong convictions and those were a product of his years of living in Nazi Germany and facing repression and a life of despair. Speier's essays compiled in The Truth in Hell, represent his work during the period 1935 to 1987 covering his life in Germany and in America. Speier was a brilliant observer of political affairs and was a renaissance man in his wide range of intellectual interests. Vidich aptly points to the deep imprint that Speier's experiences in Nazi Germany had on his thought - often leading him to a cynical Machiavellian perspective on many issues. Yet he was a man who had great spiritual consciousness and recognized that the intelligentsia is not going to show us the way out of the crisis that has left us bereft of spiritual values. According to Speier, that task "belongs to the spiritually free man who cherishes spiritual freedom." Vidich, in his introduction, gave a more nuanced view stating, "It might be added that this task belongs to the spiritually strong and the intellectually courageous, for they alone can offer us a glimpse of the world that includes irony and ambiguity unsanitized by ideological purification. This is the example that Hans Speier's work gives to us." Vidich had great admiration for Speier and his intellectual pursuits and it is truly reflected in his introduction to Speier collection of essays.

the field of sociology - especially ones that focused on his passion for community studies, politics, culture and the role of the intellectual in modern society. Many of his students asked for such favors when publishing their first book but similar requests were made by friends and colleagues who valued his professional opinion. This posting reviews three of the most significant reviews Art prepared for his close friends - Hans Speier, Ahmad Sadri and Rita Caccamo.

Intellectuals as Change Agents

Vidich wrote the introduction to Ahmad Sadri's Max Weber's Sociology of Intellectuals, published in 1992. In it he praised Sadri's gift for bringing "order to a subject that up to now has defied the best efforts of social theorists." Are intellectuals simply the product of the social and economic forces in which they live or can such persons rise above these material distractions and view the world dispassionately? In an age of propaganda driven by the vested interests of power cliques and social and political forces, it is often very difficult to determine the motives of intellectuals within our society. Sadri's book, according to Vidich, expands on Max Weber's theories concerning the role of intellectuals in modern society and establishes an entirely new framework for organizing intellectual traditions. As Vidich explains, Sadri "ingeniously provides a way to differentiate such diverse types as scientists, scholars, theorists, theologians priests, bureaucrats, media specialists, reformers, lawyers and revolutionaries by their attitude and function." While Sadri's writing may at times be ponderous, it is a masterful treatment of the role of intellectuals in modern society. As Vidich concludes, Sadri's "formulation of a heuristic general theory of intellectuals and intelligentsia is independently significant, a major contribution to contemporary social thought."

Vidich wrote the introduction to Ahmad Sadri's Max Weber's Sociology of Intellectuals, published in 1992. In it he praised Sadri's gift for bringing "order to a subject that up to now has defied the best efforts of social theorists." Are intellectuals simply the product of the social and economic forces in which they live or can such persons rise above these material distractions and view the world dispassionately? In an age of propaganda driven by the vested interests of power cliques and social and political forces, it is often very difficult to determine the motives of intellectuals within our society. Sadri's book, according to Vidich, expands on Max Weber's theories concerning the role of intellectuals in modern society and establishes an entirely new framework for organizing intellectual traditions. As Vidich explains, Sadri "ingeniously provides a way to differentiate such diverse types as scientists, scholars, theorists, theologians priests, bureaucrats, media specialists, reformers, lawyers and revolutionaries by their attitude and function." While Sadri's writing may at times be ponderous, it is a masterful treatment of the role of intellectuals in modern society. As Vidich concludes, Sadri's "formulation of a heuristic general theory of intellectuals and intelligentsia is independently significant, a major contribution to contemporary social thought."Community Studies - An Anthropologist's Perspective

Arthur Vidich praised Rita Caccamo's Back to Middletown as one of the finest examples of applying an anthropologist's "outsider perspective" to the critique of American communities. For those familiar with American community studies, the two landmark works by Robert and Helen Lynd, Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture and ten years later, Middletown in Transition (1937) established the first reference points for the decline of small town communities in America. Vidich's own work, Small Town in Mass Society, followed in that tradition so his review of Cacamo's book was more than an academic favor for a colleague. Vidich, trained both as a sociologist and anthropologist, recognized the unique insights that Caccamo, an Italian intellectual, displayed in her reassessment of Muncie, Indiana - the town the Lynd's called "Middletown." Vidich explains the unique journey that brought an Italian intellectual to study an American community that has probably been more studied and critiqued and re-critiqued of any community in America. Why do it? Caccamo's motives were multi-fold and the reader will need to read this book for the clues. Perhaps more important were her findings; she concludes that the Lynd's completely overlooked many salient trends in Muncie community life that were not pertinent to their review of the older community values. Vidich was deeply impressed by the insights that an outsider like Caccamo could bring to Middletown studies. He considered it a "benchmark study" that vies with the Lynd's original work largely due to the value of taking a fresh look at issues that only an outsider could see.

Is there Truth in Hell?

Hans Speier was one of Arthur Vidich's dear colleagues at the New School for Social Research. Hans was a man of strong convictions and those were a product of his years of living in Nazi Germany and facing repression and a life of despair. Speier's essays compiled in The Truth in Hell, represent his work during the period 1935 to 1987 covering his life in Germany and in America. Speier was a brilliant observer of political affairs and was a renaissance man in his wide range of intellectual interests. Vidich aptly points to the deep imprint that Speier's experiences in Nazi Germany had on his thought - often leading him to a cynical Machiavellian perspective on many issues. Yet he was a man who had great spiritual consciousness and recognized that the intelligentsia is not going to show us the way out of the crisis that has left us bereft of spiritual values. According to Speier, that task "belongs to the spiritually free man who cherishes spiritual freedom." Vidich, in his introduction, gave a more nuanced view stating, "It might be added that this task belongs to the spiritually strong and the intellectually courageous, for they alone can offer us a glimpse of the world that includes irony and ambiguity unsanitized by ideological purification. This is the example that Hans Speier's work gives to us." Vidich had great admiration for Speier and his intellectual pursuits and it is truly reflected in his introduction to Speier collection of essays.

Sunday, August 5, 2018

A Teacher Can Be Known by His Course Reading List

Perhaps one of the best ways to understand Arthur Vidich is to read the books that were part of his course reading lists toward the end of his life. The graduate level course "Democracy in Mass Society: The United States" was offered in the fall of 1996 and gives an excellent perspective on the ideas and analytical approaches Vidich applied to American political processes: Here is the complete reading list for that course.

Democracy in Mass Society: The United States

Department of Sociology Professor Arthur J. Vidich

The Graduate Faculty Fall 1996

New School for Social Research 4:00-5:40

GS-194

The course consists of fourteen lecture

and discussion sessions organized under seven topic rubrics listed below. The

rubrics are designed to highlight the political processes, rhetorics and mechanics

of the American democracy during this presidential election year. Under each

session’s topic heading there is one required reading and a list of supplemental

titles. Required readings and selected supplemental readings will be

distributed to the members of the course.

Course

Requirements: Each student in

consultation with the instructor will submit a research paper written on a

subject chosen from one or another of the topic rubrics. The list of

supplementary titles are provided as preliminary bibliographic references for

the research paper.

Course

Outline and Reading List

I. The

Conflation of Religion and Politics in the American Democracy.

Required:

Michael W. Hughey: “The Political Covenant: Protestant

Foundations of the American State,” State,

Culture and Society, Vol. 1, No. 1, (1985).

Supplementary:

Adam Seligman: “Inner Worldly

Individualism and the Institutionalization of Puritanism in late

seventeenth-century New England,” British Journal of sociology, Vol. 41, No.4.

(December 1991).

Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy in America

J. Fenimore Cooper: The American Democrat (Indianapolis:

Liberty Classics, 1981, pp. 12-35.

Perry Miller, The New England Mind: From Colony to Province (1953 reprint,

Boston, 1961)

Sacvan Bercovitch, The American Jeremiad, 1978, University of Wisconsin Press,

Madison, WI

II.

Characteristics of Mass Society

Required:

Herbert Blumer: The Concept of Mass

Society”, in Stanford M. Lyman and Arthur J. Vidich, Social Order and the Public Philosophy: An Analysis and Interpretation

of the Work of Herbert Blumer (Fayetteville, University of Arkansas Press,

1988), pp. 337-352 (see also pp. 35-54).

Supplementary:

Emil Lederer: Masses and Social Groups

and “The Background of Fascism,” in State of the Masses, the Threat of the

Classless Society (New York, W.W. Norton, 1940), pp. 23-68.

C. Wright Mills, “The Mass Society” in The Power Elite (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1956), pp. 298-324.

Edward Shils, “The Theory of Mass

Society”, in Fred Krinsky (ed.) Democracy

and Complexity: who governs the governors? (Beverly Hills, Glencoe Press,

1968), pp. 3-23

III.

Masses, Classes, Races and Ethnicities

Required:

Michael W. Hughey, “Protestantism and

the Politics of Diversity: Religion, Race and Ethnicity in the Ame3ircan

Covenant” (manuscript).

Supplementary:

Arthur J. Vidich, “Religion, Economics

and Class in American Politics”,

International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 1, No. 1, Fall

1978, pp. 4-22.

Michael W. Hughey and Arthur J. Vidich, “The

New American Pluralism: Racial and Ethnic Sodalities and their Sociological

Implications,” International Journal of

Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 6, No. 2, Winter 1992, pp. 159-180.

Michael W. Hughey, “Americanism and its

Discontents, Protestantism, Nativism and Political Heresy in America,” International Journal of Politics, Culture

and Society, Vol. 5, No. 4, 1992, pp. 533- 554.

Hans Speier, “Democracy and the Social

Insecurity Level” in Social Order and the

Risk of War, (Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1952), pp. 27-35

Joseph Bensman and Arthur J. Vidich,

Economic Class & Personality: in American

Society: The Welfare State and Beyond, (South Hadley, MA, Bergin &

Garvey, 1985, Chapter IV, pp. 63-86.

IV.

Democracy and the Professionalization of Political Leadership

Required:

Joseph Bensman, “The Crisis of

Confidence in Modern Politics”, in International

Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 2, No. 1, Fall 1988, pp. 15-35.

Supplementary:

Max Weber, “Politics as a Vocation”, in

Essays in Sociology, ed. By Hans H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, (New York,

Oxford University Press 1946, pp 77-128.

Joseph Bensman and Robert Lillienfeld, “Political

Attitudes” in Craft & Consciousness:

Occupational Technique and the Development of World Images, (New York,

Aldine de Gruyter, 1991), pp. 303-324

Jeffrey K Tulis, The Rhetorical Presidency, (Princeton: Princeton University Press,

1987).

V. Nineteenth Century Values: Twentieth

Century Politics

Required:

Arthur J. Vidich, “American Democracy in

the late Twentieth Century”,

International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1990, pp. 5-30.

Supplementary:

Frances Fox Piven and Richard A.

Cloward, Why Americans Don’t Vote

(New York: Pantheon, 1989)

Kathleen Hall Jamieson and David S.

Birdsell, Presidential Debates: The Challenge of Creating and Informed Electorate,

(New York, Oxford University Press, 1988).

Arthur J. Vidich, “Political Legitimacy in

Bureaucratic Society: An Analysis of Watergate”, Social research, Vol. 42, No.

4. (1975), pp. 778-811.

James Division Hunter, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define

America, Making Sense of the Battles over the Family, Art, Education, Law and

Politics, 1995, Basic Books, New York, NY

VI.

The Rules and Mechanics of Electoral Democracy

Required:

Andrew Arato, “Constitutions and the

Continuity in the Transitions”, Constellations,

Vol. 1, No. 4, 1994, pp. 92-112

Andrew Arato, “Electoral Rules,

Democracy and the Coherence of Constitutions. Theoretical Considerations and

the Case of the New Democracies”. New School,

May 1995

Supplementary:

Benjamin Ginsburg and Alan Stone (Eds). Do Elections Matter, 1996, M.E. Sharpe

Herbert E. Alexander and Anthony

Corrado, Financing the 1992 Election, 1995, M.E. Sharpe

Joseph Bensman and Arthur J. Vidich, The

Coordination of Organizations”, in American Society: The Welfare State and Beyond, (South Hadley, MA: Bergin and

Garvey, 1985), Chapter 5, pp. 87-100

John Lukacs, “Inheritances and

Prospects: The Passage from a Democratic Order to a Bureaucratic State”, in Outgrowing Democracy, (New York:

Doubleday, 1984), pp. 368-404

Eugene Lewis, American Politics in a Bureaucratic Age: Citizens, Constituents,

Clients and Victims (Cambridge, MA: Winthrop, 1977).

Robert Westbrook, “Politics as Consumption:

Managing the Modern American Election”, in Richard Wrightman Fox and T. J.

Jackson Lears (eds.), The Culture of

Consumption, (New York: Pantheon, 1983), pp. 143-173.

Murray Edelman, Constructing the Political Spectacle (Chicago: Chicago University

Press), 1988.

VII.

The Roles of public Opinion, Propaganda and the Media

Required:

Paul Cantrell, “Opinion Polling and

American Democratic Culture”, International

Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 5, No.2, Winter 1991

Supplementary:

Guy Oakes and Andrew Grossman, “Managing

Nuclear Terror: The Genesis of American Civil Defense Strategy”, International Journal of Politics, Culture

and Society, Vol. 5, No.3, Spring 1991

Guy Oakes, The Imaginary War: Civil Defense and the American Cold War Culture,

New York, Oxford University Press, 1994 (on reserve in the library).

Arthur J. Vidich, “Atomic Bombs and

American Democracy”, International

Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 8, No.3, 1995 (a comment on

Oakes’ book)

Robert Jackall, Propaganda, New York, NYU Press, 1995.

Joseph C. Spear, Presidents and the Press: The Nixon Legacy, (Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press, 1984).

Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Packaging the

Presidency: A History and Criticism of Presidential Campaign Advertising (New

York: Oxford University Press, 1984).

Saturday, August 4, 2018

Arthur Vidich Releases Multiple Books in the late 1950s and early 1960s

The years following Arthur Vidich's return from the island of Puerto Rico was one of his most productive literary periods. During the years 1957 to 1964 Art published Small Town in Mass Society with Joseph Bensman, Identity and Anxiety with Maurice Stein and David Manning White, Reflections on Community Studies, a collaborative work with Joseph Bensman and Maurice Stein as well as his classic essay titled Paul Radin and Contemporary Anthropology.

During these early years of his career, before accepting a positon at the New School, he worked on a major study of the social and psychological consequences of change in rural Puerto Rico sponsored by the Social Science Research Center at the University of Puerto Rico and funded in part by the National Institute of Health. The results of that study have never been published which is certainly a great loss for the field of sociology.

News of his prolific literary activities was big news at the University of Connecticut in the fall of 1959 - receiving front page coverage in the student paper, the Connecticut Daily Campus. While living near the rural University of Connecticut campus, Vidich was a big fish in a small pond and it was inevitable that he would soon look for teaching opportunities in a larger urban center. In 1962, Vidich was hired by the New School for Social Research in downtown New York City. It was his vision of a sociologist's Shangri-La. He remained at the New School until his retirement in 1991.

During these early years of his career, before accepting a positon at the New School, he worked on a major study of the social and psychological consequences of change in rural Puerto Rico sponsored by the Social Science Research Center at the University of Puerto Rico and funded in part by the National Institute of Health. The results of that study have never been published which is certainly a great loss for the field of sociology.

Location:

Mansfield, CT, USA

Tuesday, July 10, 2018

Arthur Vidich's Analysis of Sociology at Harvard in the Post World War II Era

In a recently discovered letter from Arthur Vidich to Professor Fred Strodtbeck written on June 12, 1991, Arthur provides an analysis of the sociology taught at Harvard and its consequences for the careers of a wide range of students who graduated from the Department of Social Relations in the early 1950s. We have provided links to the biographies of the sociologists mentioned in this letter for ease of access to the points Vidich makes. Here are the important excerpts from his letter.

June 12, 1991

Prof. Fred Strodtbeck

Dept. of sociology

University of Chicago

Social Science Building

1126 E. 59th Street

Chicago, Illinois 60637

Dear Fred:

It seems that your 20 minute assignment to talk about Harvard is taking on larger dimensions -- or, if it hasn't yet, I suggest it should. The period you are concerned with warrants expanded coverage (in the form of an intimate history) because Harvard social relations was then the one place where all the action was. During those same years, the Grand Chicago of the thirties had come apart, Ogburn taking it into a statistical mechanistic direction. At the same time, Berkeley had not yet appeared as a major Center (even though there were some outstanding scholars there). Blumer's departure from Chicago in 1954 and his appointment as Chair at Berkeley was the beginning of Berkeley's moment as the dynamic center of sociology. By that time, social relations had partly spent itself -- or, at least, had lost the elan that had been given it by the post-WWII contingent of veterans who so eagerly imbibed from the cafeteria of learning presented by the social relations staff Parsons had put together.

What is more, the period 1946-7 to 1953-5 was quite distinct from that of the mid and late thirties, immediately preceding the war. Then the stage was shared by Sorokin and Parsons -- Sorokin's mark was still left on the products of that period and Parsons did not have the sway that he succeeded in achieving later. Students during that period (among others, Robert Merton, Robin Williams, Ed Devereaux) were not exposed to the full breadth of Social Relations and it shows in the kind of work they did. Moreover, Parsons had not yet formulated a conception of a social system. Then he was still a student of Schumpeter and writing articles on capitalism while working on the structure of Social Action. (In the same apartment I found out later from him where I later lived as a graduate student -- a singular moment of intimacy in my relations with Talcott.) For Parsons, it was the war, fears of Fascism and fears for the future of the country that drove him to frame a total theory with the United States as the world's exemplar. (S.M. Lipset wrote the book The First New Nation as an ode to Parsons and in an effort to get a job at Harvard.)The social system in all its dimensions is a high-minded liberal image of what a social order should be. When Parsons spoke about racial equality, the family, responsibility and obligations, the power structure (his critique of C. Wright Mills ), the functions of the executive and all the other dimensions of American society he touched upon, he spoke from his soul -- almost as an Emersonian and certainly as a Christian ethicist concerned about the moral order of society. At the time we were at Harvard, this Parsons had not yet become the full-fledged formal social theorist he became later when four-fold tables and the harmonics of the system became almost an end in themselves - more like an ideology.

So from the perspective of your project -- and I hope that is what it is -- the Harvard period when we were there was floating with ideas going in all directions, was full of intellectual confusions and contradictions and attracted to it a remarkable collection or professors, instructors and graduate students over whom Parsons could not hold sway . All of this makes your project harder, but it is also why it makes it important -- because the after effects of people who graduated in those years are still being felt across the country.

Students of our academic generation in that period could and did respond to that environment in different ways:

1) The last of the Sorokin students (Al Pearse - in the California system - Fullerton?) spent a lot of time fighting Parsons, defending Sorokin and being ignored, and, in the case of Al, enjoying it.

2) Students (Bernard Barber) who took Parsons as the gospel -- who thought it was the ultimate truth -- followed him around with notebooks writing down his every word. This category of student probably suffered the most later on because they became attached to that Parsons from whom they learned at the time they studied with him. They then later in their careers replicated that Parsons whom Parsons no longer was -- this was a kind of mummification of ideas that for Parsons were only steps on a path to the discovery of newly emergent problems. Each stage of Parson's intellectual growth continued to exist around the country in the form of epigones who held steadfastly to what they had learned at the time they were exposed -- or we may say, catechized. (Actually, this point can be made into a more general observation about academic culture -- the same can be said for Ogborn's, Lazarfeld's or Merton's students -- i.e. , that it perpetuates a lot of dead ideas. Not much came out of this response.

3 ) Other students had the privilege of picking and choosing whom they wished to work with and which ideas they wished to attach themselves to, and went ahead and did what they wanted to do. Bob Wilson was a poet whose sociology is infused with the poet's attitude. Ralph Patrick (deceased), a Southerner struggled with the problem of race and equality and found no formula for coping with this problem. Kaspar Naegele, a poet in the mode of Simmel, knew what intellectual standards could be and anguished over his own abilities to live up to them while others (including me) thought he had achieved them: whatever caused him to commit suicide no one knows, but I think some part of his act can be attributed to the experience of being a refugee from Fascism and an intellectual at the same time. Kim Romney, a Mormon, was attracted to the architectonics of mathematics and followed Moestelar's statistical God. The Boston Irish Catholic Thomist, Tom O’Dea, was encouraged by Parsons to study the Mormons. That was good advice because it made him a sociologist and allowed him to escape from doctrinaire Catholicism. I remember discussions (deep ones) with him about faith and non-faith we were then taking life awfully seriously and thought we could find answers by studying social relations. His work is well known, original and well respected in and out of Mormon circles. There are others too numerous to mention whom I’m sure you are aware of -- and who went in their different directions reflecting themselves and not the intellectual line of an instructor or professor.

4) Harold Garfinkle whose name you mentioned in your letter is a special case -- if you wish, a type of his own (anyway there is nothing systematic or exhaustive about the typology I’ve developed, ad hoc on these pages.)

Before and while Harold was at Harvard, he became acquainted with and studied with Alfred Schutz at the Graduate Faculty, New School. (Harold and I had offices adjacent to each other and walked home together on many a day for a year to the grad student apartments where we each lived, off Brattle Street - Gibson Apartments.) It was from Schutz that Harold got his phenomenology and the problem that was to pre-occupy him the rest of his life -- his dissertation on the medical student was only the beginning. His problem in the largest sense was and is: under what conditions does a social order break down -- or under what circumstances do social relations become chaotic. Neither Parsons nor Moesteller were happy with that problem, not understanding that it was the negative side of the problem of social order for which for both of them for different reasons was the central issue (for Moesteller the harmonics of a statistical world and for Parsons the orderly performance of role functions). Harold was quite aware that his work was consistent with theirs - all he was doing was testing the outer limits of social order, but doing it in what for Harvard was a quite unconventional way (you should read the Parsons Schutz published correspondence to see how Parsons responded to Schutz - Schutz bothered him) -- Harold was trying to get into the mind, whereas Parsons wanted to manage it.

Later, maybe in 1954 or 1955, Harold spent a year of Harvard trying to integrate his work with systems theory, but nothing seems to have come of it. Nor has Harold ever said much about that. I think Harold knew that what he was doing could be made to fit the larger system as its negative counterpart, but I don’t think Parsons appreciated it. After all, Parsons was able to embrace almost everything else into his system -- the system was like a huge sponge, a niche or slot could be found in it for any new tangent, except Harold's. Explanations for this stand-off can be found, I believe, in deeper questions of religion, but this is not the place to do it, nor do I have the time to do it right, and without the implication of prejudice.

So, as a general proposition, Parson's Harvard of our period, had not yet settled into anything like the academic dogma that it had taken on later on. Students could refract off professors of their choice -- Homans, Bates, Murray, Kluckhohn, Inkeles, Moore, Paul, and even Sorokin who was still there.

Remember how physically scattered the offices of the professors were. Kluckhohn, Inkeles and Moore in the Russian Research Center. Stauffer, Parsons and Homans in Emerson Hall. The psychoanalysts and psychologists in another building. This prosaic physical fact lent a sense of freedom and lightness to academic life – you didn’t have to feel anyone was watching over you.

Put everything I've said together and it adds up to the then singular ambiance in American sociology.

(Note: a section of this letter was removed from this blog site since it dealt with personal matters).

This letter has become a little longer than I thought it would be.

Sincerely,

Arthur Vidich

cc: Bob Wilson

Stan Lyman

Sunday, January 7, 2018

Timeline of Key Events in the life of Arthur J. Vidich

1. January 14, 1920 – Joseph Vidich Jr., only three years of age, died from pulling over a

boiling pot of water. The family mourned the loss of their only son.

2. November 2, 1921 – Joseph Vidich, Art’s father becomes an American citizen.

3.

May 30, 1922 – Arthur Joseph Vidich was born in

Crosby Minnesota to Joseph & Pauline Vidich. He had three older sisters,

Pauline, Olga and Betty. He grew up in West Allis, Wisconsin living with his

parents at 5808 West National Avenue, West Allis.

4. January 19, 1938 – Art Vidich played the role of “Jim” in the three act play titled

“Treasure Island” presented at Horace Mann Junior High School. This event demonstrated

his early interest in drama and the world of theater.

5. March 14, 1940 – Art Vidich was elected a member of the National Forensic League based on

his abilities in passing national forensic contests.

6. March 18, 1940 – Art Vidich’s photo is published in the Milwaukee Journal. He is noted to

be the President of the HI-Y group in West Allis, Wisconsin.

7. May 18, 1940 –

Art Vidich receives a Hi-Y scholarship to go to the University of Wisconsin at

Madison. The award was given based on his good scholastic work, school spirit

and participation in HI-Y club activities.

8. June 6, 1940 –

Art Vidich graduates from West Allis High School. His report card for his

senior year showed he was a top notch student. He received an A in Speech and

History and a B in Chemistry, Commercial law and English. As President of his

Class, Art gave a commencement address to all of his classmates – building on

his noteworthy speech making and debate club abilities. He was one of only 45

students in his class of 372 students to receive Senior Honors (i.e., he had

grades higher than 90 over his high school years). He received the American

Legion certificate of School Award for his high qualities of character, honor,

courage, scholarship, leadership and service.

9. April 6, 1942 – Art Vidich enlisted in the Martine Corps while studying at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

10. 1943 – Both Art Vidich and Virginia Wicks were active in student politics at the University of Wisconsin. Art served on the Union Council and Virginia served on the Union Directorate.

11. April 12, 1943 – The Milwaukee Journal covers the war’s impact on the University of Wisconsin and interviews Art Vidich on his views. Art is given highly favorable coverage as follows: “Another student leader who is highly spoken about by faculty members is Arthur J. Vidich of 5808 West National Avenue, West Allis, President of the Student Directorate and a member of the marine reserves. He expects to be called to active duty in July. A serious clean cut young man, he remarked ‘Those of us who have been permitted to stay in a reserve capacity, while younger boys are doing the fighting, feel that the government wants us to remain here for special study. Under such circumstances, anybody with any conscience will work hard in the courses the military services wants us to take. I think most of the boys feel as I do about it.’”

12. April 1, 1944 – Art Vidich is assigned to Twelfth Recruit Battalion, Parris Island, South Carolina.

13. September 12, 1944 – Art Vidich promoted to Platoon Sargent and was assigned to the Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia. His promotion was coincident with his graduation from officer training school in the 53rd Class during which time he mastered 22 military courses required of Marine Corps officers including flame throwing, map reading, anti-tank rocket launcher, chemical warfare and terrain appreciation to name a few.

14. Fall 1944 – Art Vidich goes AWOL while on a trip to New York City. Due to gas rationing he was unable to make it back from a weekend furlough. As a result of this incident he was relieved of his machine instructor role at Parris Island and sent to San Francisco for deployment at Iowa Jima.

15. January 1945 – Art Vidich is promoted to 2nd Lieutenant in San Francisco before shipping out on a slow boat for Iowa Jima.

16. September 1945 – Art Vidich lands in Nagasaki just weeks after the atomic bomb struck that city and killed over 70,000 Japanese. He was assigned to the Procurement Officer of the Marine Corps with responsibility for decommissioning Japanese military equipment and coordinating the purchase of a wide range of military services.

17. January 1946- Art Vidich was assigned to Marine Corps’ Headquarters & Service & Weapons Companies, 2nd Marine Division. He remained on Kyushu Island where he continued to work as a procurement officer for the Marine Corps focused on the decommissioning of the Japanese military.

18. April 1946 - Art Vidich returns to the United States after completing his tour of duty in Kyushu, Japan.

19. June 4, 1946 – Art Vidich marries Virginia Wicks in Madison, Wisconsin wearing his military uniform (note: he was still in the Marine Corps when he got married).

20. July 2, 1946 – Art Vidich receives an honorable discharge having achieved the rank of 1st lieutenant in the Marine Corps. His official reason for leaving the Marine Corps was to pursue a Master’s degree at the University of Wisconsin.

21. September 1947 - Art Vidich leaves for Palau to conduct anthropological research for the United States Navy’s Office of Naval Research and the National Academy of Sciences.

22. 1947 to 1948 - Art and his wife Virginia collaborate on a paper titled, Gerald L. K. Smith Speaks at Viroquia; a social psychological study in public opinion. Hans Gerth, Art’s mentor at the University of Wisconsin, provided support for this work. This would later become a paper prepared by Virginia Vidich titled Gerald L. K. Smith Speaks at the Cross Roads; a social psychological study in public opinion.

23. May 24, 1948 – Charles Vidich is born in Madison Wisconsin while his father was away in Palau on an anthropological expedition.

24. June 27, 1948 – Art arrives in Fairfield, California, on a United States Navy aircraft after spending nearly a year completing anthropological research in Palau.

25. August 17, 1948 – Art Vidich receives a Master’s of Science in Anthropology from the University of Wisconsin based in part on his thesis titled “The American Success Dilemma.”

26. September 1948 – Art enters Harvard University’s program in Social Relations where he studies with Clyde Kluckholn, Talcott Parsons and Barrington Moore. He receives a Thayer Scholarship for 1948-1949 as one of a limited number of meritorious Harvard students.

27. June 1949 – Art publishes a Navy funded study titled “Political Factionalism in Palau: Its Rise and Development” which was sponsored by the Pacific Research Council and the National Research Council.

28. May 25, 1949 – Art passed a special exam for a PhD in Social Anthropology at Harvard after completing eight courses in Social Relations and Anthropology with distinction.

29. August 11, 1950 – Paul Vidich, Art’s second son is born in Mount Auburn hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

30. September 27, 1950 – Art, Virginia and their two boys arrive in Southampton, England on the Queen Elizabeth where Art spends the year at the London School of Economics on a Fulbright fellowship.

31. October 4, 1950 – The Milwaukee Journal announces that Arthur Vidich is one of 500 Americans to receive a Fulbright scholarship to study at the London School of Economics. He is one of 58 Harvard students granted this award.

32. October 23, 1950 – Art writes to Joseph Bensman to let him know that during his first nine days in London he, Jij and the boys lived in a hotel due to a severe housing shortage in London. Fortunately, he found an apartment in a former mansion in Hyde Park and his Fulbright stipend allowed him to hire maids and baby sitters for his two boys – Charles and Paul.

33. Spring 1951 – Art and Virginia visit their relatives in Kropa and receive an overwhelming welcome. They leave their children with a nanny in London.

34. June 11, 1951 – Art and Jij write to the Bensman family about life in London and their plans to visit Yugoslavia during the summer. Art acknowledges getting the contract to complete interviews of the radio listening habits of Slovenes for the Voice of America during his planned three week stay in Yugoslavia.

35. June 27, 1951 – Art arrives in Yugoslavia with his family and declares this to be a real vacation. He tells Joe Bensman in a letter of this date that he plans a trip to Zagreb to conduct interviews for the Voice of America.

36. July 25, 1951 – Art writes to Joe Bensman indicating he is writing up the interviews that he was contracted to complete for the Voice of America.

37. Summer 1951 – Art and Virginia return to Kropa with many sorely needed goods requested by their relatives. Art conducts clandestine interviews for the Voice of America on the radio listening habits of the Slovenes.

38. August 10, 1951 – Art and his family depart from England on the S.S. Mauretania bound for the port of New York and arrive August 16th and are met by Joe Bensman.

39. Fall 1951 – Art accepts a three year position as the Assistant Professor and Resident Field Director, Cornell University, 1951-1954. He rents a house in the town of Candor, New York where he conducts seminal research on small town politics that will eventually lead to the publication of his classic book, titled “Small Town in Mass Society.”

40. March 31, 1952 – Art submits his Ph.D. thesis in Social Anthropology to the Department of Social Relations, Harvard. The thesis is titled “The Political Impact of Colonial Administration.”

41. May 22, 1952 – Art passed his final examination for a PhD in Social Anthropology

42. January 3, 1953 – Andrew Vidich is born in Ithaca, New York, Art’s third son.

43. June 1953 – Harvard Department of Social Relations confers a PhD in Social

Anthropology to Art

Vidich.

44. August 1954 – Art and his family fly to San Juan Puerto Rico where he was offered a position at the University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras. He meets many new people who become his life-long friends including Virginia Betancourt (daughter of Romulo Betancourt, President of Venezuela), Eugenio Granell (a gifted Spanish painter and social thinker), Franz Von Lichtenberg (a world renowned tropical medicine physician who later was appointed professor of Tropical Medicine at Harvard Medical School) Mohini and Balaji Monkur, Kurt and Edith Bach (Kurt Bach was an MIT trained psychologist) and Leopold Kohr (an Austrian economist and proponent of small-size states who had a profound influence over such thinkers as British economist E. F. Schumacher and his book “Small is Beautiful” whose title was derived from Dr. Kohr’s writings).

45. December 1955 – Art takes his family on a vacation to St. Croix, the American Virgin Islands where they meet a man who single handedly paddled a dugout canoe from Africa to this Caribbean island. He departs for his home in Rio Piedras on January 4, 1956 flying on Caribbean Atlantic Airlines with his wife and three boys.

46. January 27, 1956 – Art writes to Joseph Bensman about his forthcoming publications. He mentions that Virginia has taken a job to earn extra money. He dreads taking on domestic duties stating “With Jij working, life has become crazy as hell. Even with her making three hundred bucks in two weeks, it begins to seem it’s just not worth it. For one thing, I have had to domesticate myself again and having been out of the routine for a year and half, it’s difficult.”

47. May 31, 1956 – Joseph Lucian Vidich, Art’s 4th son, was born in Rio Piedras with a tooth in his mouth at birth.

48. Summer of 1957 – Art accepts a position as Assistant Professor at the University of Connecticut. He rents a house in Ashford, CT on Wormwood Hill Road located on a large farm.

49. Fall of 1957 – Art’s classic book, Small Town in Mass Society is published by Princeton University Press. Favorable reviews appeared in Commentary and Political Science Quarterly

50. November 5, 1957 – University of Connecticut President Jorgensen announces the hiring of Arthur Vidich as a professor of Sociology and Anthropology. He also notes his teaching experience at Cornell, Rochester and the University of Puerto Rico along with his work at Harvard’s Social Relations Laboratory.

51. July 25, 1958 – Art buys the former home of Dr. Raymond Wallace located at 1637 Storrs Road, Storrs, CT containing 1.07 acres. The house remained in the Vidich family until 1995 when Virginia Vidich passed away.

52. March 3, 1958 – Dennis Wrong at Brown University writes an exceptionally favorable review of Small Town in the New Leader. Wrong states “It pains me to have to report that the virtues of this book are exceptional in the works by contemporary sociology. For as I am sure Vidich and Bensman would agree, their achievement is not so extraordinary as to be beyond the level of competence which one is entitled to expect from any properly educated modern sociologist. But their book is exceptional. Let us hope that it will start a trend, or more accurately, a counter-trend.”

53. September 1958 – Esther E. Twente at University of Kansas provides a favorable review of Small Town in Mass Society as a descriptive study of Springdale illustrating the dichotomy between the values and attitudes of the people in relation to their own image and the reality values and attitudes imposed upon them by the forces of mass society “makes for an intriguing story both for the lay reader and for one with a professional interest.” However, Twente suggests the authors failed to address the impact of mass society on the family as a primary social institution. She also thought the authors should have provided a brief statement of their methodology and a bibliography (note: this latter point was addressed in a later edition of the book).

During this same month

Edmund Brunner at Columbia University reviews Small Town in Political Science Quarterly and declares

the volume “interesting, intriguing and irritating.” Brunner claims the authors

fail to consider the reciprocal relationship of Springdale to Mass Society

where interdependence is greater than “sinking into the slough of dependence.”

He also suggests that the author’s unstated values have biased their

perceptions of how Springdale residents accept their defeat to the values of a

mass society. On the positive side Brunner lauds the authors for their deep

probing that goes far beyond others in challenging conventional theories of

politics and culture in small town America.

Finally, Noel P. Gist at the University of Missouri reviews Small Town

in The Annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science. Gist praises the book by stating “This is

exemplary social science community research. It is also a tribute to the

resourcefulness of the authors.”

54. 1959 – President Romulo Betancourt pays a private visit to Art Vidich at his home in Mansfield, Connecticut following his visit to the Rockefellers. Betancourt was a family friend and his daughter, Virginia, was one of Art’s students at the Universidad de Puerto Rico.

55. February 1959 – Harold Orlans at the National Science Foundation reviews Small Town in Mass Society and People of Coal Town (Harold Lantz) in the American Anthropologist in which he pans the latter book and raves over the former. In Orlans dismissing Lantz’ study states “It is a startling contrast to find in Small Town in Mass Society one of the most original and perspicacious community studies yet published. While Orlans faults Vidich and Bensman for lacking an empirical base, he contends they pass “two critical tests so many social science generalizations fail: it is convincing and it adds to our understanding.” He concludes by saying that Small Town “...testifies to the authors’ achievement that their examination of a small New York community illuminates aspects of human life anywhere.”

56. November 2, 1959 – The Connecticut Daily Campus (CDC) newspaper announces that Art Vidich is studying the social and psychological consequences of change in rural Puerto Rico with support in part from the National Institutes of Health. The CDC also notes Vidich is working on a book titled “Identity and Anxiety” and an Introduction to the Method and Theory of Ethnology.

57. May 13, 1960 – Art Vidich leads a faculty opposition to the expulsion of Richard McGurk, editor of the Connecticut Daily Campus, from the University of Connecticut. McGurk was held responsible for allowing quasi pornographic material to be published by his staff – an annual practice of the Connecticut Daily Campus staff coincident with the April 1st issue. Vidich enlists the support of 101 other faculty to call for his re-enlistment and to drop all of the charges against him. The petition is signed by dozens of faculty who are close friends with Art and Virginia Vidich.

58. 1960 – Art collaborates with Maurice Stein and David Manning White as an editor of Identity and Anxiety, a collection of 41 essays on various aspects of identity and anxiety in mass society written by some of the leading thinkers of the 20th century.

59. 1960 – Art accepts a teaching position at the New School for Social Research in New York City and begins a long period of commuting to the City while his family lived in Storrs, CT. He would come home on weekends. During this time he also accepts a visiting professorship at the Florence Heller School of Social Work at Brandeis University requiring him to visit to the University every Monday during the period 1960 to 1966.

60. March 1961 – Daniel Miller of the University of Michigan reviews “Identity and Anxiety” in the American Journal of Sociology and deems the author’s conclusions as “depressing.” He notes that the “political and social upheavals of our time… represent such pervasive and overwhelming threats to the stable identity that…. it almost appears as if the anxiety they arouse can only be managed by defensive apathy.” Despite Miller’s inability to grasp the significant impact this book would have on the academic world, he does a marvelous job of summarizing the key points made in the 41 essays contained in this 658 page book.

61. July 24, 1961 – Art and Virginia Vidich buy a log cabin that is located immediately behind their home in Mansfield, Connecticut. The land and home was purchased for $1,540 from Raymond Wallace. Art rents out the log cabin to various professors working at the University of Connecticut as a means to increase his cash flow.

62. Summer 1962 – Art’s father and mother and his sister Elizabeth come to visit him in Mansfield, CT along with Elizabeth’s nine children. It would be the largest gathering of the Joseph and Pauline Vidich’s clan in the 20th century.

63. Spring 1963 – Art starts working at Clark University in Worcester as a visiting Professor – a stint that last until 1966.

64. 1963 – Art collaborates with Maurice Stein and publishes Sociology on Trial with Prentice Hall. This edited book contains 11 essays on the philosophical underpinnings of sociology as a discipline and becomes an important critique that gains an international following with translations of the work into other languages.

65. 1964 – Art is appointed Chairman, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, New School for Social Research, Graduate Faculty from 1964 to 1969. During this year he collaborates with Maurice Stein and Joseph Bensman on a book titled Reflections on Community Studies, published by John Wiley & Sons.

66. Summer of 1964 – Art travels to Bogota Colombia for a six month sabbatical where he is a visiting Professor of Sociology, Universidad Nacional, Bogota, Colombia. He returns to the United States in January 1965 with his entire family in tow. During this time, his wife completes PhD research on infant mortality in Colombia.

67. March 1965 – Jack Rothman at the School of Social Work, University of Michigan praised Reflections on Community Studies as “provocative and absorbing. I especially recommend the volume to doctoral students setting out to attack a dissertation. It will help bring out some of the inevitable personal considerations accompanying social research, thus serving as beneficial counterpoint to more usual readings dealing with statistical and research design issues.” Rothman, despite this praise, felt the book did not stick to its theme in all of the essays contributed by a half dozen sociologists.

68. April 1965 - Charles Wagley at Columba University praises Reflections on Community Studies as “an interesting and refreshing book” and as one making “an important contribution in a neglected area of sociology and anthropology.” The reviews appeared in the American Anthropologist a year after this book was published.

69. May 1965 – Bennett Berger at the University of California Davis reviews Sociology on Trial in the American Journal of Sociology. Berger claims the book is a collection of essays critical of the dominant figures and schools of thought in sociology. He faults several of the essays for their combative style and the making of paper tigers out of some establishment sociologists and their theories (e.g., Parsons). Berger accepts some of the moralistic passion against establishment sociology shining through the contributor essays but warns that professional courtesy and respect should be offered to such establishment types in the interest of pursuing the truth rather than ad hominem character assassinations. Overall Berger believes the authors have over characterized the American Sociological Association members as establishment types – even though he recognizes that class of sociologist exists.

70. May 1965 – Selz Mayo reviews Reflections on Community Studies in the May issue of Social Forces and suggest the book would have been better titled “Confessions on Community Studies” in light of the tone of several essays. Nevertheless Selz appreciates the author’s concern with narrowly focused community studies attributable to the bureaucratic constraints of government grants that fail to capture the experiences within a community. The methodological insights provided in this book, he believes are all case specific and do not rise to the level of universal methodological insights.

71. October 1965 - J.R. Treanton reviews Reflections on Community Studies in the French publication titled Revue Française de Sociologie, and declares it to be an excellent collection of essays.

72. December 1966 – Art is appointed Advisory Editor to Appleton Century Crofts in Anthropology and Sociological Theory.

73. May 1968 – Art drives to Waltham with Paul, Andrew and Joe to meet Charlie and informs them that he has separated from Virginia.

74. June 11, 1968 – Art confides to Joseph Bensman about all the work it takes to get his three sons prepared for their trips to the Mediterranean (Paul) and South America (Charles and Andrew). He confesses, “… once they are gone, I’ll have a chance to get down to some of my own work.”

75. February 27, 1969 – Art Vidich and Mary Gregoric make application for a mortgage for the purchase of a 3,360 square foot townhouse located at 40 Bedford Street, New York.

76. August 1, 1969 – Virginia Vidich obtains a divorce in Tolland County Superior Court. Virginia is given custody of the children but later events alter this court order.

77. September 22, 1969 – Art marries Mary Rudolph Gregoric.

78. September 1969 – Art accepts position as Visiting Professor, New College, Sarasota, Florida, 1969-1970. His son Andrew lives with him in Sarasota while his youngest son, Joseph, remained with his mother in Connecticut.

79. September 16, 1969 – Art’s mother Paulina passes away in Ashland, Wisconsin while staying with her daughter Betty. She died at the age of 77.

80. 1971 – Art collaborates with Joseph Bensman and publishes The New American Society with Quadrangle Books.

81. March 1972 – Mayer Zald at Vanderbilt University reviews The New American Society in the American Journal of Sociology. Zald praises the author’s analysis that connects self-esteem and personal style to positional and institutional change. However, he pans the book as lacking intellectual rigor and footnotes.

82. 1973 – Art is appointed as a Member, Editorial Board, Journal of Political and Military Sociology. This same year he is appointed an Editorial Advisor, John Wiley and Sons.

83. March 1973 – Frank Coleman at the State University of New York of Geneseo reviews The New American Society in the March 1973 issue of American Political Science Review (Vol. 67, No. 1, p. 214) and focuses on the author’s analysis of capital and its impact on American society. Coleman notes the author’s thesis points to the importance of the “socialization of the use capital corresponding to the activity of the state as an instrument of capital accumulation.” Coleman is not entirely convinced of Art’s analysis but concludes that “this essay is nevertheless recommended for its illuminating treatment of the social effects of changes in the position and the form of capital in America from the 1940s to the present.” Coleman’s review brought an entirely different perspective to Vidich’s work than that set forth by Zald the previous year. One might actually think these reviewers read entirely different books! Indeed, such disparate reviews points to the breadth of analysis and intellectual appeal of the themes contained in this book.

84. June 1973 - Art accepts an appointment as a Senior Fulbright Lecturer at the University of Zagreb, Yugoslavia – a position he holds until January 1974.

85. June 9, 1975 – Art joins the Harvard Club of New York City.

86. September 1977 – Art accepts a fall semester position as Visiting Professor, University of California, San Diego, Department of Sociology, September-December, 1977

87. Summer 1978 – Art accepts summer position as Distinguished Lecturer, Kyoto-American Studies Seminar, Kyoto, Japan.

88. July 7, 1979 – Art accepts summer position of Breman Professor of Social Relations, University of North Carolina, Asheville, July 7-August 10, 1979.

89. April 21, 1980 – Art and Mary sell their townhouse at 40 Bedford Street to Christopher Jeans & Jessica De Grazia giving the buyers a mortgage which was finally paid off on July 18, 1997.

90. 1980 – Art publishes his Ph.D. dissertation titled “The Political Impact of Colonial Administration” through Arno Press, a New York Times Company.

91. December 1983 - Don Martindale at the University of Minnesota reviews Politics Character and Culture; Perspectives from Hans Gerth in the December 1983 issue of Social Forces. Martindale quibbles with some of the author’s opinions concerning the impact of Gerth on his disciples (i.e., namely on Martindale himself!) but concludes that “No student of social theory and of the history of social thought can afford to ignore this book.”

92. 1985 – Art collaborates with Stanford Lyman and they publish American Sociology; Worldly Rejections of Religion and Their Directions through Yale University Press.

93. 1985 – Michael Grimes at Louisiana State University reviews American Sociology in Social Science Quarterly. Grimes concludes that “this book joins a growing list of recent works which provide important insights into the field and should be added to the reading agenda of all those interested in the nature of sociology as an intellectual enterprise and its practitioners.”

94. September 20, 1985 – Alan Sica at the University of Kansas reviews American Sociology in Science. Sica says that from a Weberian perspective sociology was a religion by another name. Sica faults the authors for their selection of sociologists they analyzed and for over-emphasizing the Protestant influence upon earlier sociologists based merely on a review of certain works without regard to whether such works were representative and without disentangling their religious phraseology typical of the 19th century from their actual religious convictions.

95. December 1985 – Thomas Haskell at Rice University reviews American Sociology in the Journal of American History and concludes that the book is a “speculative reassessment of the place of sociology in American culture.” Haskell faults the authors for their lack of knowledge of historical and cultural landscape in which American sociology developed. He also finds fault with their assessment of Puritanism as the intellectual origin of sociology when in fact it is more closely connected to Christianity.

96. February 1986 – James Beckford at the University of Durham reviews American Sociology in the Journal of the British Sociological Association proclaiming that the “originality of their work lies in its relentless and absorbing documentation of the many sided connection between the Christian religion and the problematics of classical American sociology.” He further states “the history of sociology was badly in need of their irreverence and iconoclasm.”

97. March 1986 – Lewis Coser at the SUNY Stony Brook reviews American Sociology in the American Journal of Sociology and blasts the authors for their sloppy work, selective presentation of the historical evolution of American sociology and their inclination toward “Parsons bashing.” Coser, with a personal axe to grind, concludes that “critical thought on the history and present state of the sociological enterprise does not need hanging judges but scholars whose work meets the highest professional standard.”

98. March 1986 – Charles Page at the University of Massachusetts reviews American Sociology in Contemporary Sociology. While Page slights the author’s overemphasis on religious determinism and fails to consider the impact of Jewish and European sociologists in shaping American Sociology, he concludes by saying “I strongly recommend this erudite, provocative and indeed enchanting book to all serious students of American sociology. Those who fail to read it will be losers.”

99. Summer 1986 – Jessie Bernard at Pennsylvania State University reviews American Sociology in the Sociological Forum and praises its stance in favor of the heterodoxies of modern sociology including the growth of women’s studies. Bernard finds ample justification for rejecting past religious and chauvinist based sociological theodicies. She titled her review/essay “American Sociology as Moral Life.”

100. December 12, 1986 – Art delivers a eulogy for Joseph Bensman at City University of New York praising his intellect and his will to live during his last few months of hospitalization at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York City.

101. 1987 – Art and Joe Bensman publish American Society; the Welfare State and Beyond which is a republication of their earlier work on The New American Society.

102. January 1987 – Susan Henking of Chicago reviews American Sociology in the Journal of Religion and faults the authors for their monolithic view of Protestantism and their limited historical insights about the history of the protestant faith and how it influenced the development of sociology. She also contends the authors were neither historians nor theologians since their analysis fails to capture the insights those disciplines might bring to the topic. That said, Henking considers the book a “welcome addition of the place of religion in the history of the social sciences….”

103. Spring 1987 – James Casey at the University of Illinois, Chicago reviews American Sociology in the spring 1987 issue of Sociological Analysis and quibbles with the author’s perspective that Harvard’s social theorists were the driving force for social science in the pre 1950s era – asserting that the University of Chicago was sociology’s national center. Despite the quibbles he thinks “their fundamental thesis is provocatively stated and suggests that now that we’ve exorcized our Puritan past we are ready to develop a science of society appropriate for a modern industrial age.”

104. Fall of 1987 – Art establishes the International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society with an Editorial Board composed of himself, Stanford Lyman and Michael Hughey and 23 Advisory Editors.

105. January 1988 – James Rule, at SUNY Stony Brook gives a generally positive review of American Sociology although he questions the book’s length (i.e. 300 pages). Rule states, “At best, this book is an illuminating look at intellectual and cultural forces whose role in shaping the study of society has been poorly understood. At worst, it is a one-argument book whose single argument is made to carry more weight that it can bear.”

106. January 27, 1988 – Reporter Michael Gulachok of the Tioga County Courier analyzes Small Town in Mass Society and its impact on the town of Candor and its prominent residents.

107. Winter 1988 – Henrika Kuklick from the University of Pennsylvania reviews American Sociology: Worldly Rejections of Religion and Their Directions and faults the authors for not consulting works that would have permitted them to assess their subjects in a comparative framework. Nonetheless Kuklick finds the book enjoyable if one is looking for incidents in the history of the social sciences which its practitioners would like to conceal.

108. March 1989 – Lester Kurtz at the University of Texas at Austin reviews American Sociology in the Sociological Forum along with several other books. He proclaims American Sociology an “outstanding work” and lauds the authors for their effort to free sociology of the “iron cage of its past origins.

109. Summer 1989 – Art takes his three grandsons, Josh, Jamie and David to get haircuts and lollipops in Stafford Springs, CT some ten miles from where his son Charles lives in Connecticut. This event, while mundane in scope, left a deep impression on his grandsons who reveled in his affection for them.

110. January 1990 – Mari J. Molseed at Pennsylvania State University reviews Social Order and the Public Philosophy: An Analysis and Interpretation of the Work of Herbert Blumer (1988) in the American Journal of Sociology. Molseed commends the author for their “imaginative treatment of the issues of freedom and constraint as being central to social order” and the necessity for a public philosophy that incorporates the ideas of freedom and democracy without undue state intervention in these processes.

111. Summer of 1992 – Art retires from the New School and is appointed Professor Emeritus of Sociology and Anthropology.

112. 1992 – Art becomes a co-founder of the Institute for the Study of Contemporary Society and the International Thorsten Veblen Association.

113. 1993 – Art moves to Southampton, New York commuting to New York City once a week to give a course in his role as an emeritus professor at the New School for Social Research.

114. 2000 – A.J. Veal at the University Technology, Sydney reviews American Society; the Welfare State & Beyond and notes that it is a republication of Art and Joe Bensman’s previous publication titled, The New American Society.

115. 2002 – Nicholas Goetzfridt and Karen Peacock publish Micronesian Histories: An Analytical Bibliography and Guide to Interpretations in which they reference Art’s seminal study titled “Political Factionalism in Palau: Its Rise and Development” and note its singular importance as a guide for understanding the impact of American foreign policy on traditional Palau political and cultural values.

116. March 9, 2003 – Stanford M. Lyman passes away after contracting liver cancer. Art Vidich praises Stan as a brilliant intellectual with over 25 published book and over 100 articles including their joint venture – American Sociology. Two months after Stan’s death, Art prepared a eulogy honoring his dear friend for his wide ranging intellectual knowledge. He also acknowledged it was because of their joint effort to protect the accreditation of the New School’s sociology department from an anti-European bias of the accreditation board that they both wrote American Sociology.

117. September 10, 2003 – Mary Rudolph passes away from complications related to Parkinson’s disease. Her children take her body in a station wagon and deliver it to the Rudolph family cemetery in the Midwest.

118. March to June 2005 – Jamie and Josh Vidich spent several months with Art after Mary passed away. Art’s two grandsons were very helpful during this trying transition period in his life.

119. March 16, 2006 – Art passes away in his home at 7 North Sea Road, Southampton, NY after several years of battling neuropathy - a disease that may have been triggered by his exposure to the nuclear radiation from the atomic bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki in August 1945. Art was cremated and his ashes were dispersed in Long Island Sound

120. September 15, 2006 – The New School convenes a memorial conference on Arthur Vidich and his intellectual legacy which is attended by over 50 faculty, students, friends and family.

121. 2008 – The New School establishes the Arthur J. Vidich Dissertation Fellowship.

This fellowship benefits students working on their dissertations in sociology at the New School for Social Research, with priority consideration given to students pursuing topics that were of major interest to Dr. Vidich. These include but are not limited to community studies, bureaucracy in modern society, the student of American culture, and international culture and politics. Special consideration will be given to students who pursue such interests through fieldwork.

122. 2009 – Art’s autobiography is published by Newfound Press. Editorial work on the book was provided by, among others, Robert Jackall, Joshua Vidich and Jamie Vidich.

123. November 2012 – David Kettler of Bard College writes a magnificent and glowing review of Art’s book, With a Critical Eye – An Intellectual and His Times which appeared in the Contemporary Sociology a Journal of Reviews. Kettler stated “Observation rather than theory was his métier.”

124. June 2015 – Charles M. Tolbert at Louisiana State University reviews The New Middle Classes: Life Styles, Status Claims and Political Orientations (1995) in the Journal of Sociology and & Social Welfare. Ten years after Vidich edited this collection of essays, Tolbert undertook a critique of his work and suggests that the middle class is shrinking and therefore future studies should focus on its decline rather than on its emergence. He notes that most of the essays deal with the middle class prior to the 1980s and therefore the book does not capture major changes in the middle class – including its decline - over the last 20 years.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)